A new platform has been developed to provide Spanish-speaking doctors with an opportunity to work while waiting for their qualifications to be verified by the United States Medical Licensing board.

Intermeds, a program funded by the Productive Development Committee of Antofagasta in northern Chile, allows patients in South America to carry out a consultation with doctors in the United States.

The initiative has the potential to help up to nine million people in the region who are waiting to see a medical professional said entrepreneur Carlos Araya, the brains behind the Intermeds project, to Miami Herald.

Despite an increase in healthcare spending and a demand for doctor consultations, Chile suffers from a shortage of specialists in isolated regions such as Antofagasta. Patients from these regions are forced to travel to the capital, Santiago, in order to receive the consultation they require. This trip can cost upwards of $250, not including accommodation, food, and additional expenses. Patients who cannot afford this are placed on a waiting list, which can be as long as two years.

A study carried out by Alejandro Letelier and Gustavo Cifuentes Rivas revealed that patients were forced to wait between 150 and 500 days to receive treatment. Furthermore, an investigation by the World Bank and Chinese Health Ministry discovered that the Chilean public health sector had a 40 percent shortage of physicians

In the U.S., and Florida in particular, Latin American doctors who have immigrated find themselves unable to contribute to the healthcare sector, despite holding qualifications from their home countries. Many of these doctors work as in areas completely outside their profession, whilst awaiting validation.

Previously, attention has been raised regarding the shortage of Spanish-speaking doctors in the area. Many patients feel more comfortable consulting with a physician who speaks the same language as they do, yet many doctors still find themselves out of work.

Organizations such as the Chicago Bilingual Nurse Consortium look to help professionals in these types of situations by offering support in passing the National Council Licensure Exam. The test prep has helped over 250 internationally educated nurses, but the process still takes as long as four years.

Other programs include Florida International University, which retrains immigrant doctors as nurses to deliver diversity to the healthcare workforce, as well as assisting in treating minority patients.

Araya describes the platform as ‘an information service for patients’. Those who use the service will be placed in touch with a doctor remotely who can then carry out preliminary examinations, provide a second opinion, and make decisions on what the patient needs to do, or what needs to be done.

However, Araya stresses that the report should serve purely as a recommendation, and that patients should always attend local medical services for treatments. This is due to a ruling by Brad Dalton, Deputy Press Secretary of the Florida Department of Health, that any practices of medicine must be completed by a practise licensed by the local government.

“The Florida Statutes define ‘Practice of medicine’ as the diagnosis, treatment, operation or prescription of any human disease, pain, injury, deformity, or other physical or mental condition,” Dalton told the Miami Herald.

Doctors who register with Intermeds are able to access medical records of patients online, as well as undertake videochats and give their opinion.

Araya has already come to agreements with three public hospitals in Peru to accept Intermeds reports. A review of the legality of the project concluded that it is possible to implement Intermeds in Mexico and Argentina, in addition to Peru, although Araya still faces problems. In Chile, consultation requires validation before the patient’s primary doctor signs the report.

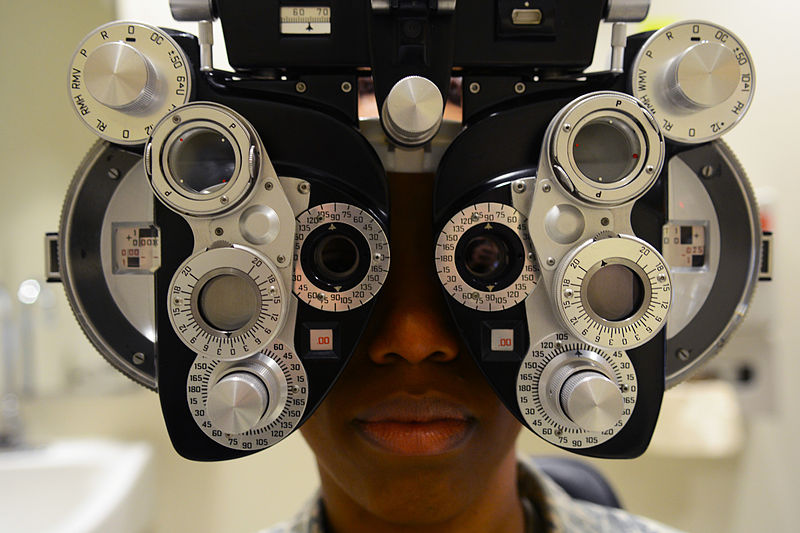

The first area Araya and Intermeds is tackling is ophthalmology, which has been identified as having the longest waiting list in Chile. The team is reaching out to ophthalmologists in the Miami area, which shares the same time zone as Chile, to take part in the pilot phase of the program. In addition to this, there are also plans to open an office to receive phone calls and meet with doctors.

“The good part of ophthalmology is that with four or five tests more than 99 percent of the cases can be diagnosed,” said Araya. “There can be very accurate tests.”

This will represent a more simplistic approach to tackling healthcare issues in Chile. By focussing its attention on easy-to-solve but heavily backed-up problems, Araya and team can legitimize their platform, whilst also assisting patients who potentially could be waiting up to two years to be seen – by which point, problems could have escalated.

Consultations will cost $100, which is the average cost of a private visit in Chile, but minus travel expenses. Doctors will receive $16 per report, whilst some of the revenue will be used to subsidize patients who are on the waiting list, but cannot afford to see a specialist. Special attention will be made to the older patients on the waiting list. Extra money will be focused on maintaining the Intermeds platform.

Araya’s aim is to benefit both doctors and patients together, using a platform that is sustainable, without relying on funding from the government. The platform is a further example of Chile’s gradually growing innovation scene. A potential push-back from healthcare professionals is something Araya is aware of, but he stresses he is concerned only with finding the best doctors to assist with helping the people.

“We are looking for doctors who want to help with a social cause,” he said.